Clinical research asks questions about how well an investigative treatment or diagnostic works, or how well and in what amounts existing treatments work by comparison. But, with a broader view, clinical research can do more. If research is aligned to address areas of high unmet need and disease burden, society can begin correcting pre-existing health disparities. Clinical research has the opportunity to build outreach efforts that provide communities with understandable, relevant information about their health and health care—and science writ large—and can give them the tools to evaluate future advances. There is an opportunity to build research that co-creates with communities, prioritizes efforts based on local needs and preferences, and disseminates innovation. Research has the capacity to build new avenues into care as people actively participate in trials, and, with that, in their care and in their health.

But to bring communities along on this journey, research must be able to reach them. The Milken Institute’s 2024 report Distance as an Obstacle to Clinical Trial Access: Who Is Affected and Why It Matters illustrates distances by county to the closest clinical research site and documents the widespread problem of research access. Access is strikingly different in different parts of our country and for different diseases. For many diseases, there are locations that are both far away from a relevant clinical trial and that have an extremely high prevalence of that disease.

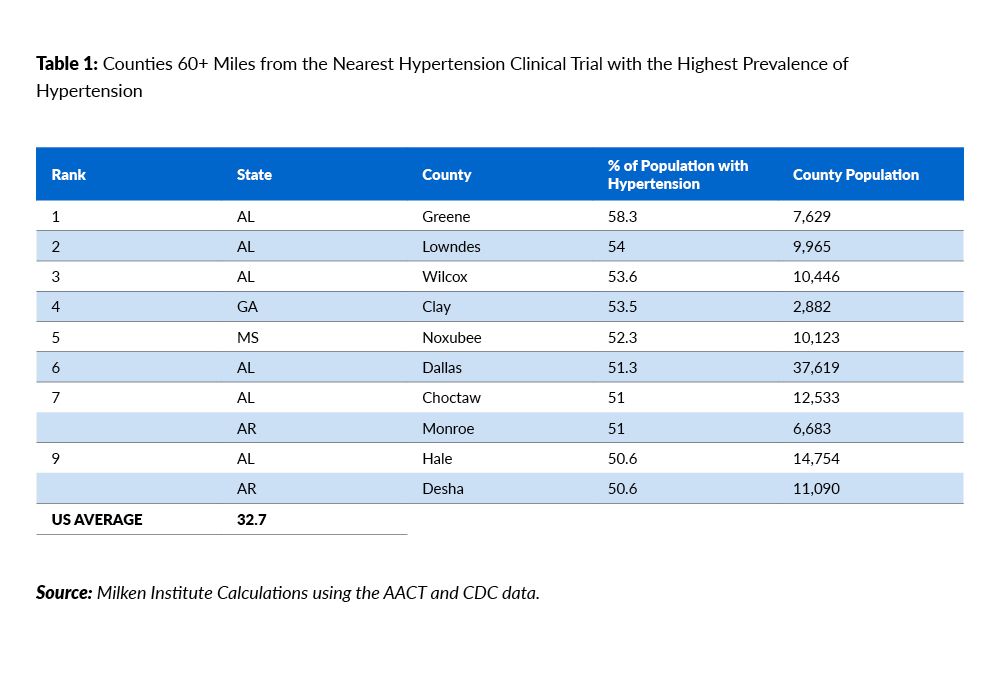

For example, using the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative’s Aggregate Analysis of ClinicalTrials.gov database, we identified every US county that was over 60 miles away from the nearest clinical trial for a drug treating hypertension that was started between January 1, 2017, and September 30, 2023. Then, using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s PLACES data, we identified the ten counties with the greatest prevalence of hypertension that are also over 60 miles from the nearest relevant trial (Table 1).

But what does this mean for a patient? In the counties shown in Table 1, the incidence of high blood pressure is over one and a half times the US average. About every other person in these counties suffers from high blood pressure. While many treatments for high blood pressure work well, controlling it depends on the ability to support recommended lifestyle changes, regular access to care, careful monitoring and dosing, and consistent adherence to medications, according to the Mayo Clinic. Only 25.7 percent of hypertension cases are under control. Many patients have resistant hypertension, where even a combination of standard medications plus lifestyle changes have no effect on blood pressure or have comorbidities such as kidney disease that affect how well medications work and which ones are safe. Additionally, research demonstrates that people of different racial backgrounds may metabolize common medications differently.

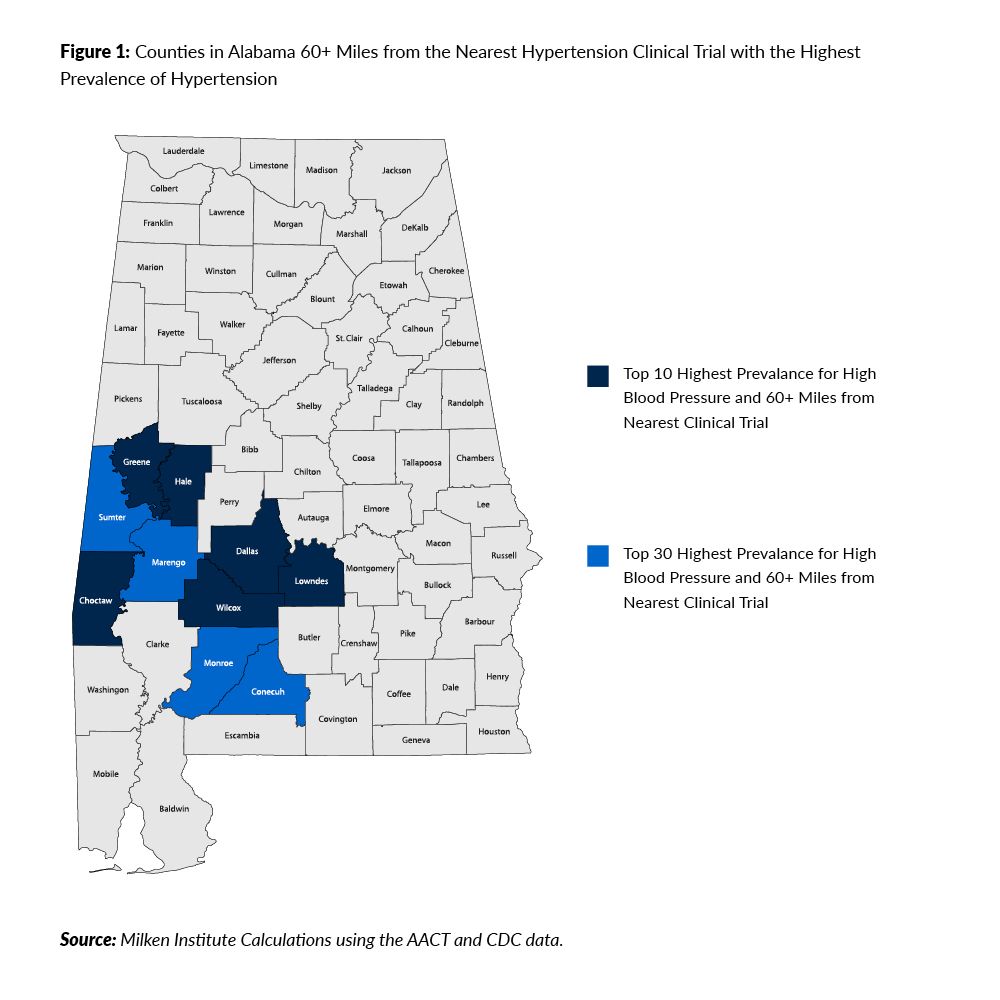

The Alabama counties outlined in Table 1 are geographically proximate. If we expand the list to the top 30 counties with the highest prevalence, there are an additional four proximate southwest Alabaman counties (Figure 1) with dramatically increased hypertension prevalence.

In this cluster, clinical research options are limited for patients who struggle with their existing medications, who are looking for another avenue to care, who want to contribute to our collective knowledge and understanding of medicine, or who want to contribute for the sake of their families. One of the closest sites running hypertension trials is in Birmingham (Shelby County). For a person living in Wilcox County’s seat of Camden, the drive to the University of Alabama Birmingham Hospital is about 125 miles or 2.5 hours. From Choctaw’s county seat of Butler, it’s about 150 miles and 2.5–3 hours. From Hale County’s seat of Greensboro, it is 90 miles and about 1.5 hours.

For these counties with high disease burden, the driving time to Birmingham is 1.5–3 hours one way. The burden of participating in a trial in these places is enormous—three to six hours of driving time alone, not even considering the time required to park and attend the trial appointment. Add to that that trial appointments may only be available during working hours, so each appointment necessitates a longer-than-full day off work and away from family and responsibilities. For trials that require frequent site visits, this becomes burdensome even for patients with jobs that have ample paid sick time.

But what if instead, this is recognized as a hot spot for decentralized trial activity? Decentralized trials conduct some portion of trial activities away from a traditional trial site. This could mean using a heart monitor to collect data at home, visiting a local doctor’s office to get vital signs checked, having blood drawn at a local lab or pharmacy, or many more variations. In this case, hypertension might be suitable for a trial that has some decentralized elements that are tailored for the disease, available diagnostics, and technologies, and to the patients and providers in question. A trial like this could still be primarily run out of Birmingham, where the primary investigator for the trial works, and trial logistics and oversight are coordinated. That primary investigator in Birmingham could then partner with regional clinics in Wilcox County. Those local clinics have long stood in those communities and are staffed by people who understand which community events matter and which local organizations are meaningful. The trial could free up resources for routine screenings as part of community events or partnerships with local organizations. Perhaps some attendees realize that they have untreated hypertension or that their medication is not working as well as they thought.

If most of the follow-up or monitoring trial appointments are done at these locations, driving distances could be greatly reduced to closer to three miles (about 10 minutes of drive time). Consultation and simple trial appointments like blood draws can happen over a lunch break. Perhaps a trial participant could pick up the trial medication at their local pharmacy or have it delivered to their home. They could still go to the site in Birmingham to meet the primary investigator and complete complex procedures, but that would occur once or twice a year rather than frequently. The time cost of participation would be vastly reduced, making participation more realistic for more people.

There is evidence that decentralized trials can offer a good return on investment or improve their representativeness. Based on this illustration, decentralized trials can greatly improve access in some of the most underserved locations. Decentralized trials have the potential to help bend the curve of life expectancy and help our neighbors and ourselves live longer, fuller lives.