Throughout the world, women’s entry into the labor market is an essential catalyst of economic growth. According to estimates from the World Bank, achieving gender parity in employment could increase the world’s income by almost 20 percent (or over $20 trillion, in total). As highlighted in our recent report, increasing women’s workforce participation is especially essential to the growth of Latin America’s five major economies—Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Colombia—that jointly generate 80.8 percent of the region’s gross domestic product. Despite achieving continuous progress in incorporating women into labor in the past, the rate of women’s entry into the workforce has slowed, nearly stagnating more recently in these countries. Female labor force participation rates in all but one (Brazil) of Latin America’s major economies remain below the region’s average and below the rates of Southeast Asian nations such as Japan, which achieved impressive economic growth thanks to women’s entry into labor from 2012 to 2019, as reported by the International Monetary Fund.

To illustrate, consider the case of Mexico, the US’s southern neighbor and main source of imports of goods. Mexico's labor market represents a duality: a strength and a challenge in the country's sustained growth. While surpassing most other key US trading partners (except China and Brazil) in terms of labor potential, the low participation of women in the Mexican labor market limits the size of its workforce.

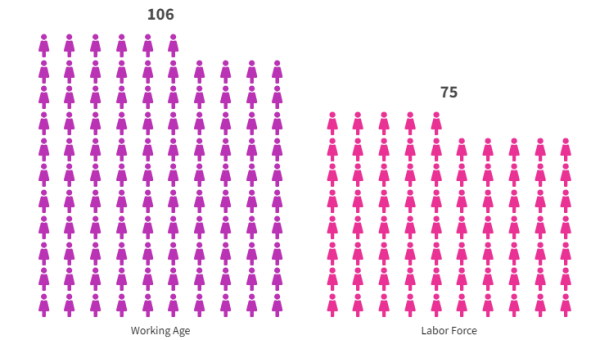

Recent industrial growth has led to a deficit of skilled workers in Mexico, strengthening the importance of incorporating Mexican women into remunerated employment. In 2022, there were 106 women for every 100 men with advanced education in Mexico. Yet only 75 of these highly skilled women were in the labor force.

Figure 1. Women per 100 Working-Age Men (Mexico)

Source: Milken Institute analysis using data from the ILO (2024)

Mexico needs its women to join the workforce to solve its skilled labor deficit. According to projections of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Latin America has reached the limits of its male labor contribution, and in Mexico, men’s labor force participation rates are above the region’s average. Women are both qualified and willing to contribute to Mexico’s skilled talent: 64 percent of women in this country say they want to work, either exclusively or in combination with house care, according to a survey conducted by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in conjunction with Gallup. What, then, is keeping Mexican women (whose labor force participation rate is only 45.7 percent) out of remunerated work?

While no single reason can fully account for Mexico’s low female labor force participation rates, two contributing factors that stand out are domestic pressures and low access to highly paid formal jobs. About a third of Mexican prime-aged women (ages 25 to 49) list unpaid home care as their main activity, compared with less than 1 percent of men, according to data from the ECLAC. This is higher than the rates reported by similarly aged women in comparable Latin American economies, such as Brazil and Argentina, where only 17.6 percent and 18.2 percent of women report unpaid home care as their main activity, respectively.

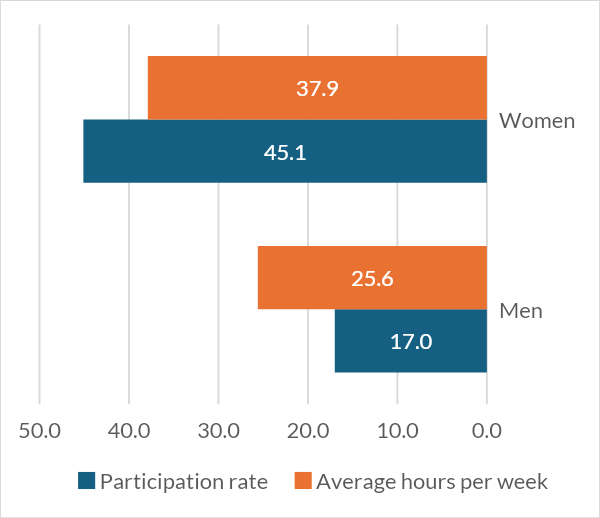

Figure 2. Participation in Unpaid Activities, by Gender (Mexico)

2a. Prime-Age Population in Unpaid Activities (%)

2b. Participation and Time Spent in Dependent Care

Source: Milken Institute Analysis using data from the ECLAC and the ENASIC 2022 survey

Data from Mexico’s Encuesta Nacional para el Sistema de Cuidados (ENASIC) confirms the high house care pressures on Mexican women: 37.9 percent of women (compared with 25.6 percent of men) provide unpaid care for a dependent such as a young child or an older adult. Moreover, of those who provide care, women spend more time than men doing so, with almost a full workweek (or 40 hours), spent on dependent care by female unpaid care providers. In this context, policies such as childcare subsidies, the expansion of public preschools, and cost remedies that result in access to free or low-cost childcare stand out as particularly important in Mexico. These policies have consistently been identified as successful in increasing levels of women’s work and promoting growth by research from the Inter-American Development Bank and Banco de México, among others.

Second, according to ECLAC data, many women in Mexico still lack sufficient access to high-paying formal employment. Despite there being 9 Mexican women for every 10 men employed in high-skilled occupations, women are more likely to earn low wages, with 20.3 percent of women, compared with 13.1 percent of men, paid less than two-thirds of the median income. Moreover, a large portion of highly educated Mexican women have had to resort to informal employment to manage remunerated employment with domestic pressures. While informal employment rates are high among both men and women in Mexico, female informal workers have higher educational attainment. Transitioning skilled female workers into the formal economy would have important fiscal, social, and economic benefits for Mexico.

To conclude, Mexico needs its women, and women need Mexico’s government and businesses to invest in services that expand their access to employment. To be successful, policies and labor market interventions should address the multiple constraints to women’s work. A holistic approach includes the expansion of access to low-cost and high-quality dependent care, the creation of formal jobs with flexible schedules, and the battle against gender discrimination. Through such interventions, Mexico would capitalize on its investments in female education and position itself on a path of sustained and inclusive growth.