“We examine the different fiscal stimulus measures African governments have deployed in an effort to combat the economic repercussions of this global pandemic.”

As the UNECA’s Dr. Vera Songwe told COVID-19 Africa Watch in June, the COVID-19 pandemic arrived in Africa first as an economic crisis, then as a health crisis. The health crisis arrived first elsewhere—in China, Europe, and the United States—and the shockwave of the shuttering of those economies reached African countries before the full force of the virus did.

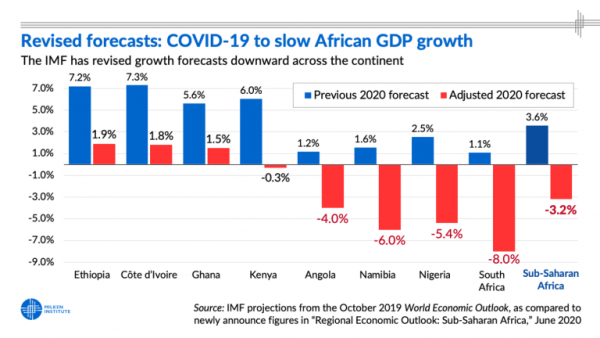

The result for Africa has been the beginning of the first major recession for the region in over 25 years. The IMF now projects the regional GDP of Sub-Saharan Africa to decline by 3.2 percent, compared to a previously projected growth of 3.6 percent—a considerable negative swing of 7 percent. In some countries, the economic downturn has been even more pronounced. In South Africa, the IMF is projecting a contraction of 8.0 percent; the Nigerian economy is expected to shrink by 5.4 percent; and in Botswana, the IMF anticipates a 9.6 percent contraction.

Across the continent, African governments have responded the best they can to this reversal of fortune with various policy initiatives. Forty-five African governments have announced some form of fiscal stimulus in response to the pandemic. The largest, both in its U.S. dollar value and as a percentage of national GDP, has been South Africa’s, at about US$38 billion (based on an exchange rate from earlier this year) or roughly 10 percent of GDP.

However, for the most part African governments simply lack the fiscal space to provide the kind of stimulus deployed in advanced economies. The median stimulus package for the region was only 1.5 percent of GDP. Only two other African countries—Sierra Leone and Seychelles—have had stimulus packages of over 5 percent of GDP. By comparison, the COVID-19 stimulus package in the United States was 13.2 percent of GDP, and in the U.K., it was 7.4 percent.

In addition, in Africa, as elsewhere around the world, passing these plans required extraordinary legislative sessions and changes to existing budgetary rules. Many African countries repurposed their existing budget plans and reduced the capital expenditures to ease up the fiscal pressures and adopted supplementary budgetary laws to streamline the necessary response funding. For the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), it was necessary to suspend the fiscal deficit rule in order for member countries to borrow more than 3 percent of GDP to finance the necessary stimulus responses.

In a previous note, we looked at the monetary policy response to COVID-19. Below, we examine the different fiscal stimulus measures African governments have deployed in an effort to combat the economic repercussions of this global pandemic. The spending and policy categories discussed here are drawn from our fiscal policy monitor, which we have kept updated continuously since March of this year.

What was in these stimulus plans designed to mitigate the negative impacts of COVID-19? The measures can be divided into three broad categories. First, support for businesses included tax relief, subsidies, financing support measures, and specific initiatives designed to bolster SMEs. Second, support for household included cash transfers, food assistance, and individual tax relief. Third, new health spending was incorporated into many African budgets as a response to the pandemic.

Below, we look at each of these categories in more detail, before briefly addressing the role that multilateral institutions played in the fiscal response.

Support for Businesses

Corporate tax relief: Over 40 African countries have broadly adopted some form of targeted temporary tax reduction, deferral, or moratoria measure, in addition to lowering VAT and import duties, and waiving late payment fines and penalties. Ethiopia, for example, declared tax amnesty to all corporate tax debts that occurred before 2019, while Senegal suspended tax payments up to 24 months and allowed write-offs of certain kinds of tax debts. Botswana provided one of the largest tax deferrals, allowing businesses to defer 75 percent of tax payments to 2021. Nigeria and Zambia relieved tax penalties and fees for hard hit sectors. Many countries, including Congo, Chad, Ethiopia, Eswatini, DRC, Malawi, Mauritania, Somalia, South Africa, Togo, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, exempted or reduced import tax duties for medical supplies and essential goods, such as rice and food items.

Corporate subsidies and other support measures: Thirty-four countries implemented some form of corporate guarantees or provided subsidies, lowered government licensing fees, or suspended regulatory inspections, among other corporate support measures. Many countries targeted support measures toward strategic sectors, such as agriculture and food supply (as Burundi, Chad, and Côte d’Ivoire did, for example), and hospitality and tourism (as in Egypt, Seychelles, and Mauritius). Half of the Egyptian stimulus package was devoted to the tourism sector and to providing subsidies for exporters. The Ethiopian government arranged free railway transportation between Ethiopia and Djibouti to streamline the cross-border trade process.

Financing support measures: A number of countries provided corporate financing support to help keep businesses afloat during the economic downturn caused by the pandemic. Governments in Botswana and Gabon, for example, provided a direct financing or loan guarantee from the pooled resources by the government and local banks. Mauritius also implemented need-financing support measures. The Mauritius State Investment Corporation planned Rs 4 billion ($100 million) equity investments for troubled corporates, while Mauritius Development Corporation is providing Rs 200 million ($5 million) short term liquidity cash injections.

SME support measures: While a number of African countries created SME support guarantee funds (Mali, Mauritania, and South Africa), other countries provided a direct liquidity subsidy or subsidized loans to their troubled SMEs (as did Rwanda, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe). Some notable examples include Lesotho, which provided a M450 million (about US$26 million) loan guarantee facility for SMEs and helped clear existing arrears. Meanwhile, Ghanaian authorities created a first-loss guarantee instrument to protect SMEs in the country. Among other SME support measures, Chad reduced business licensing fees by 50 percent for SMEs in 2020, while Lesotho’s local authorities offered grants and rent subsidies to their troubled SMEs. The Gabonese government provided about US$200 million (1.3 percent of GDP) for SME support measures, including subsidies on electricity and water payments. Guinea also exempted utility bills of troubled SMEs in the hospitality and tourism sector.

Support for households

Cash transfers: In response to rapid lockdowns, thirty-six African countries announced various cash transfer programs for vulnerable households. These transfers help families provide for urgent needs during lockdowns and job losses. In South Africa, which has also had one of the continent’s most restrictive and prolonged lockdowns, the government announced one of the most comprehensive emergency grant programs, covering 44 percent of households, proving R350 (about US$20) a month to all unemployed citizens between the ages of 19 to 59. Egypt announced the targeted cash transfer program that provided EGP 500 (US$32) for 3 months and increased the pensions by 14 percent for 1.6 million recipients. Cameroon increased the initial monthly cash allowance from CFAF 2800 to 4500 (US$5-8) to most vulnerable families. Malawi directed US$50 million (0.6 percent of GDP) of donor funding to emergency cash transfer programs.

Food assistance: To address increased food insecurity, eighteen African countries have implemented nationwide emergency food distribution programs. In some countries, a sizable percentage of the population required emergency food assistance. For example, The Gambia distributed food assistance to around 84 percent of the vulnerable households (1.9 million people). Eswatini’s food assistance program reached 26 percent of the population (300,000 people), and Ethiopia’s food support reached 14 percent of the population (15 million people), while Kenya distributed food assistance to over 8% of the vulnerable population (3.8 million people).

Individual tax relief: Several African countries extended tax relief to individuals as well as to businesses, and others are currently considering plans to do so. Morocco, for instance, allowed tax exemptions for up to 50 percent of monthly salary and allowed households to defer income tax payments until September 30, 2020. Kenya relieved personal income taxes for those who earn $225 per month or less, regardless of sector, while Rwanda only allowed personal income tax exemptions for hospitality and school sector employees. Many countries, including Algeria, Ethiopia, Morocco, Namibia, and Rwanda, have extended filing deadlines for last year’s personal income taxes.

Interestingly, at least two countries introduced new taxes as part of their coronavirus response. Egypt imposed a coronavirus tax of 1 percent on all salaries, while São Tomé and Príncipe introduced solidarity taxes on public sector employees who have not been affected by pandemic-related layoffs.

Additional healthcare spending

At least 39 African governments expanded healthcare spending packages to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. The largest package was in Sudan, where the government announced SDG 30 billion (about US $542 million) or 1.6 percent of GDP, to prevent the collapse of the country’s health system. Likewise, Togo, CAR, and Seychelles announced multiyear programs that accounted for more than 10 percent of government budget spending planned to strengthen the healthcare sector and pandemic response capability. Many countries—including Eswatini and Gabon—redirected low priority budget spending to healthcare response.

Initial healthcare spending focused on purchasing essential medical supplies and equipment, building quarantine facilities, among making other investments in the healthcare sector that would strengthen response capabilities. Ghana, for instance, indicated they needed to upgrade over 100 hospitals. Another key line item has been hiring and training healthcare professionals. For example, Angola budgeted around $80 million to retain 250 doctors from Cuba. A number of countries, including Nigeria, built coronavirus isolation and treatment centers.

The role of multilaterals

The IMF and World Bank have played an important supporting role for many of the new spending measures described above. In the first few months of the pandemic, the IMF’s financial support for fiscal budget and balance of payments needs for African countries surpassed US$28 billion, and 33 African countries received funding through IMF’s Rapid Credit Facility or other financing instruments. At the same time, the World Bank has been instrumental in supporting the socio-economic and emergency health response for over 34 African countries, providing $6.8 billion in support to African governments, often as grants. Over 30 African countries benefited from the World Bank’s COVID-19 Fast Track Facility program to strengthen their healthcare response measures. Perhaps the most prominent example is Ethiopia, which received $82.6 million for public health, emergency medical supplies, and diagnostic capacity-building programs as part of its National Preparedness and Response Plan for COVID-19.

For more details on which African countries have received financial support from multilaterals, visit our Global Response Funding Tracker.

Closing thoughts

It is probably too early to know how effective the policies surveyed above have been in containing the economic damage of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly as the global health crisis appears to be far from over. Likewise, we already know through several high-profile examples that the success of some of these programs has been marred by corruption. What is clear, though, is that many African governments responded quickly and robustly to a truly global threat. In terms of the health crisis, this response seems to have reaped dividends. The outcome of the economic story, though, remains unclear.