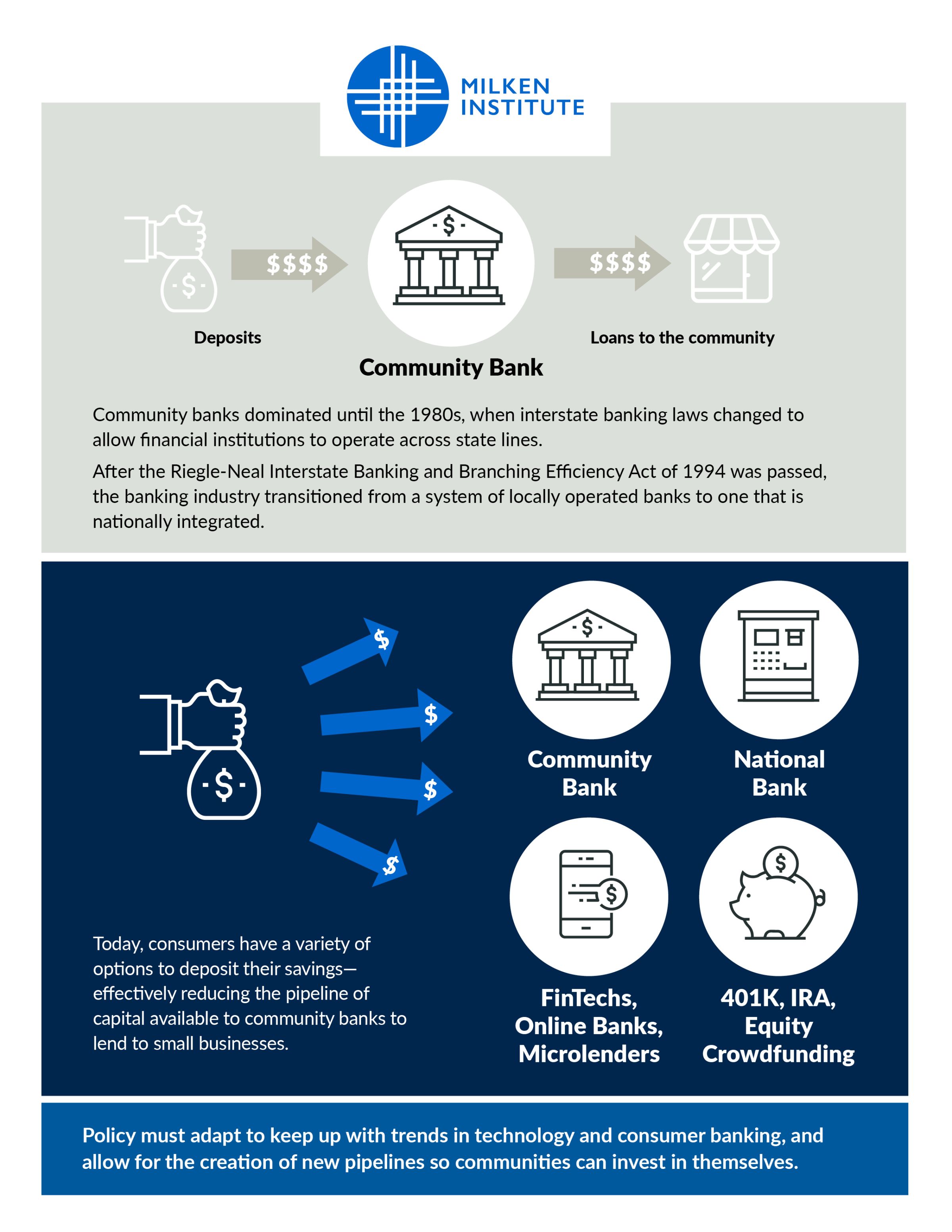

In Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, as George Bailey tries to prevent a run on the Bailey Brothers Building and Loan, the audience receives a lesson in community banking and the economic multiplier effect. Customers deposit their savings at the bank, which are then lent to others in the community. It’s a delicate but virtuous economic cycle.

Much has changed since this timeless classic was released in 1947. The modern banking system is far more complex and decentralized. As interstate banking laws evolved, paving the way for consolidation, the number of community banks was dramatically reduced. This trend ultimately increased the distance between lenders and borrowers, both physically and relationally. People now have a wide range of options for depositing and investing their savings beyond their local bank. Meanwhile, businesses have moved online, and there are fewer locally owned options in most cities and towns. The net effect of these shifts is that less money organically stays within a community. Yet the need for capital has never diminished.

Policymakers have focused on using equity crowdfunding for early-stage, high-growth startups. The Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act created a way for small and emerging companies to issue securities through equity crowdfunding. There has been less focus on how it could help facilitate capital formation for Main Street small businesses and other ventures that are not quite ready to be priced for equity.

Non-equity and pooled crowdfunding have the potential to re-establish the pipelines to keep more capital circulating within a community and close this funding gap. I propose expanding current legislation to permit crowdfunded pooled funds organized around specific themes, such as geography or sector, and crowdfunded loan funds. Allowing for this type of syndicated fund structure could establish a new, more efficient pipeline for crowdfunded capital to flow within communities. Just as municipal bonds facilitate investment in public infrastructure, legislation needs to allow for the creation of funds that specifically invest in a cross section of local small businesses.

Microlending platforms and other FinTechs have addressed some gaps in small business lending created by the reduction in community banks. These platforms often derive the bulk of their capital through government programs, such as the Small Business Administration or Community Development Financial Institution Funds, or from banks fulfilling their Community Reinvestment Act obligations. Non-equity crowdfunding platforms like Kiva provide crowdfunded microloans, but only on a company-by-company basis. This is an inefficient way to invest in a cross-section of small businesses and creates undue concentration risk for investors. I propose expanding the JOBS Act to allow a fund structure that syndicates both the demand and supply sides of capital.

The high risk associated with investing in startups and small businesses is often cited as the reason to limit crowdfunded investment options. This argument overlooks a key tenet of modern portfolio theory: idiosyncratic risk is generally lower if it’s a diversified portfolio. Increasing the number of companies or investments within a portfolio typically lowers its overall risk. For example, a fund that invests in twenty local restaurants would be less risky than investing in just one. Amending the crowdfunding legislation and regulations to allow investment syndication could lower the overall risk of crowdfunded investments through diversification and expand access to capital for a broader range of small businesses.

Regulatory risk concerns also ignore the fact that most people want to invest in small businesses for reasons beyond financial return. Small businesses provide a variety of social and economic benefits that are simply not captured by the mathematical rate of return. It’s hard to quantify the positive externalities that neighborhood shops and a robust downtown area provide to a community. Allowing community members to more directly and efficiently invest in their communities is a form of economic development.

Consider a scenario where there is a common need for capital, such as after a natural disaster like Hurricane Helene in Asheville, NC. After the storm, there were investors who wanted to provide capital to a cross-section of local restaurants, but their only available options were donations to individual GoFundMe pages or general small business grant funds. Imagine how much more capital could be raised for small businesses if individuals were able to invest in the sectors that align with their interests via a pooled fund that allows them to potentially recover their investment? Both investors and small businesses would benefit from this new type of fund structure, which could create a much-needed new capital pipeline.

While efforts have been made to create community investment funds, I believe these proposed changes would go further and better align with modern investor objectives. Today’s investors expect to be able to invest in the themes, causes, or places that suit their individual preferences and investment objectives. It’s why there are thousands of unique public funds, and it has helped equity crowdfunding thrive since its launch in 2016. These financial structures allow people to customize their investment portfolio; we believe it’s time to let them diversify as well.

The laws and regulations around capital formation have simply not kept pace with the evolution of how individuals want to save and invest, the state of community banking, or the available technology to do so. Nearly 99 percent of all businesses in the United States are classified as small businesses, and access to capital is the number one challenge most small businesses face. Isn’t it time for policy to catch up with economic realities?